As a baseball fan, it comes naturally to second guess the decisions made by the manager. As a Mets fan dealing with Terry Collins this year … let’s just say there have been too many of these opportunities this season. Whether it was his handling of the lineup (starting Justin Ruggiano and Ty Kelly over Michael Conforto and Brandon Nimmo) or leaving in Jay Bruce to run for himself in the ninth inning of a one-run game, Terry Collins has made many questionable decisions. But some of the decisions that puzzled me the most surround his usage of the bunt. The whole idea of bunting dates back to the 1880s and has been around for about 130 years, however the usage of the bunt in more recent years has become ever more controversial. That is because using the statistical evidence that is now available; bunting gives up an out and thus the statistical likelihood of scoring runs decreases. However, to many in the non-sabermetric population the preference of the bunt makes sense. For example, a sacrifice bunt with a runner on first and no outs means that you will have a runner at second with only one out if executed successfully. This means that you avoided the double play and that potentially only a base hit would be required to get that runner in from second.

This is the thinking of the past and Terry Collins and the Mets coaching staff should try to move away from this thinking, especially when they have Noah Syndergaard and Steven Matz trying to bunt when they have had success hitting in the past. The Mets so far for 2016 rank 11th in the National League (and 12th in MLB) in terms of usage of sacrifice bunting–they have utilized it less than the rest of the league. Still, there have been multiple late-game decisions to bunt that were absolute head scratchers that led me to write this article. To explain the theory of why the Terry Collins’ reckless decisions to bunt have had negative impacts on the likelihood of the Mets winning ballgames I will use two different examples:

- August 1 – Matt Reynolds sacrificed James Loney over to third base with no outs in the bottom of the 10th trailing the New York Yankees by one.

- August 10 – Travis d’Arnaud attempted to sacrifice bunt T.J. Rivera to second base with no outs in the bottom of the 10th inning with the game tied.

Run Expectancy Theory

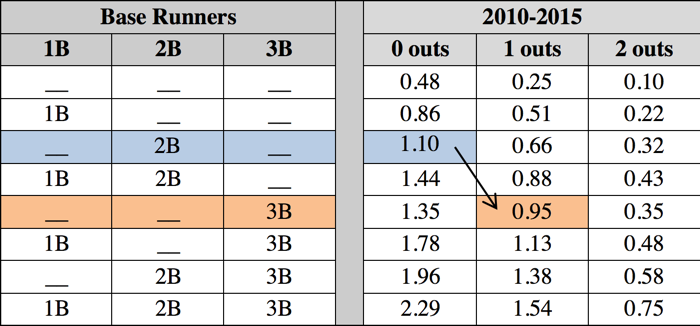

In the book properly titled: The Book: Playing the Percentages in Baseball by Tom Tango, Mitchel Lichtman, and Andrew Dolphin, a discussion is had on how the number of runs expected to score in an inning is impacted by two main factors: the base or bases that runners are currently positioned and the number of outs in the inning. As there is not enough data available for 2016–it is less than a full season–and the run expectancy table is available for 2010 to 2015, I will use the run expectancy table for 2010-2015 to evaluate the decisions made by Terry Collins in these two situations.

August 1 – Bottom of the 10th, Matt Reynolds vs. the Yankees

First, let’s evaluate the Mets decision to bunt with Matt Reynolds on August 1 trailing the New York Yankees by one in the bottom of the 10th inning. For the purposes of this discussion we won’t even take into consideration that James Loney–one of the slowest runners on the team–was the baserunner. We’ll start by taking a look at the following table:

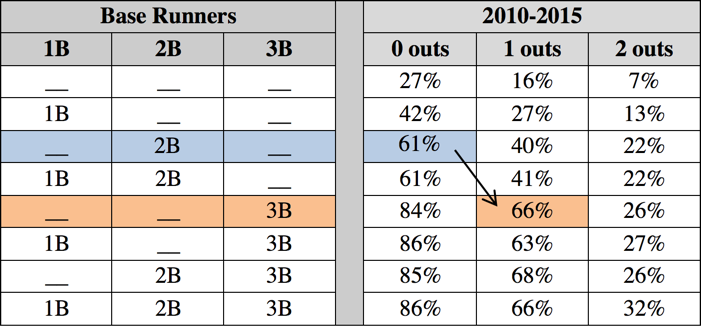

The two highlights represent the states that the Mets were in prior to Matt Reynolds’ sacrifice bunt (highlighted in blue) and where the Mets ended up after Reynolds sacrificed Loney over to third base (highlighted in orange). As we can see, the Mets went from a run expectancy of 1.1 runs to a run expectancy of 0.95. Given that the Mets were trailing by one run in the bottom of the of the 10th, they needed to score one run just to tie the game and extend it … but needed two in order to win the game, which should have been the goal of that inning. Therefore, bunting in the situation the meant that the Mets’ win expectancy according to FanGraphs actually decreased from 41 percent to 39 percent. That’s a small change, but the goal is to win games–especially when trying to get a Wild Card spot it seems odd that the Mets would try for the tie. Matt Reynolds was two-for-four that game with a home run which makes the decision to have him bunt even more puzzling. If the Mets goal was to tie that game then this decision might make sense. Look below:

As seen from the table above, the Mets’ percentage chance of scoring a run that inning actually increased from 61 percent to 66 percent. While it could be argued that Terry preferred to just get one run home and try to win it in the next inning, the logic still seems a bit dodgy. From the perspective of a manger trying to win rather than just trying to extend the game, it clearly makes sense to not sacrifice in this situation. And although the bunt was successfully executed, the Mets were not able to score the necessary run as Rene Rivera grounded out to Betances and Curtis Granderson struck out to end the ball game. The bunt “worked”, but did not actually achieve the intended purpose of getting the tying run home. An even more clear situation would be when the Mets needed to score only one run to win the ballgame. And that is what occurred on August 10.

August 10 – Bottom of the 10th, Travis d’Arnaud vs. the Diamondbacks

On August 10, the New York Mets managed to tie the Arizona Diamondbacks in the bottom of the ninth inning when Kelly Johnson crushed a two-run homer into the Coca-Cola Corner. In the top of 10th inning Jeurys Familia held the Diamondbacks scoreless and gave the Mets a chance to win it. To start the inning, T.J. Rivera singled to center on a ball that Michael Bourn almost had difficulty handling. Up next was Travis d’Arnaud. Despite him having a down season, he had been hitting relatively well in August. However, instead of letting d’Arnaud try to get a hit and help the team, Terry Collins thought it would be best to have him attempt to bunt Rivera over to second avoiding the double play and putting the winning run in scoring position. d’Arnaud was unable to get a proper bunt down and ended up popping out to first base. This meant that bunt actually did not accomplish anything other than giving the Diamondbacks a free out. But the question is whether d’Arnaud should have been bunting in the first place.

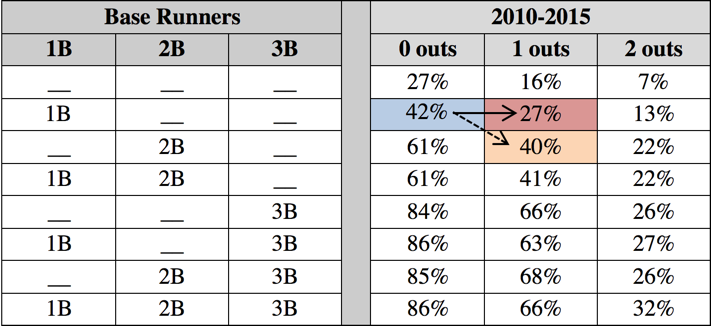

The whole purpose of having Travis d’Arnaud bunt was to score the one single run that was necessary to win the game. But even if d’Arnaud was able to successfully get the bunt down, the Mets’ chances of scoring a run that inning would have further decreased from 42 percent to 40 percent. This is not a significant change, but it meant that bunting and giving up an out had a negative impact on the likelihood of the Mets scoring a run. The Mets seem to have had plenty of bad luck this season, and the plan did no go how it was supposed to. This meant that d’Arnaud bunting had the same impact as any other out and dropped the Mets’ chances of scoring a run that inning down to 27 percent. While I will admit that this outcome was still better than a double play, it is not a good situation when the manager does not trust a hitter of d’Arnaud’s caliber to hit the ball successfully. Of course, the rest of the game did not go according to plan. James Loney grounded out and Alejandro De Aza flew out to end the inning. The Mets ultimately lost in 12 innings, but might not have if they had not chosen to give away an out when they had a chance to win.

Conclusion

While the New York Mets–as of writing this piece–had bunted 34 times (based on data from Statcast/Baseball Savant), this only includes bunts that were successfully dropped down to sacrifice over a runner or popped out with runner on base. This does not include events such as Noah Syndergaard bunting into a double play due to a failed sacrifice or Matt Harvey striking out trying to bunt with two strikes. The amount they have struggled bunting this season has been overwhelmingly frustrating as a fan. These Mets are giving away outs in a season when every out counts. Hopefully someone sits the Mets coaching staff down this winter and shows them the math on how bunting is actually impacting their chances of scoring a run and their probability of winning. Once they understand and embrace the math can they finally start making smart baseball decisions.

Photo Credit: Brad Penner-USA TODAY Sports

1 comment on “How Not To Bunt (A Run Expectancy Tale)”

Comments are closed.