“Just throw strikes, kid. We can’t afford to give out any free passes! Throw strikes and the rest will work itself out.” This sounds like basic advice to give to a pitcher like Zack Wheeler, who has the seventh highest walk rate of any National League pitcher with at least 70 innings pitched. Before Wheeler’s last start, manager Terry Collins told the media that the big thing Wheeler needs to do is start throwing his breaking pitches for strikes. Now, let’s play a little game. Which of these Mets’ pitchers lead the starting rotation in percent of pitches located in the strike zone, according to PITCHf/x?

Jacob DeGrom

Robert Gsellman

Matt Harvey

Seth Lugo

Noah Syndergaard

Zach Wheeler

deGrom leads the rotation with 51.9 percent of his pitches in the zone. Wheeler is actually close behind him at 51.5 percent; in fact, he’s tenth highest throwing pitches in the strike zone out of the 60 National League pitchers who qualify. (Measuring the strike zone is still an imprecise science. Baseball Info Solutions’ tool has Wheeler ranked #21 – still above average and better at finding the strike zone than any other Met starter.) And while Wheeler doesn’t have the biggest sample size post-Tommy John, it is large enough that we can tell he has basic control. He’s not the type of pitcher you need to yell at to “just throw strikes.” But he still walks a ton of batters.

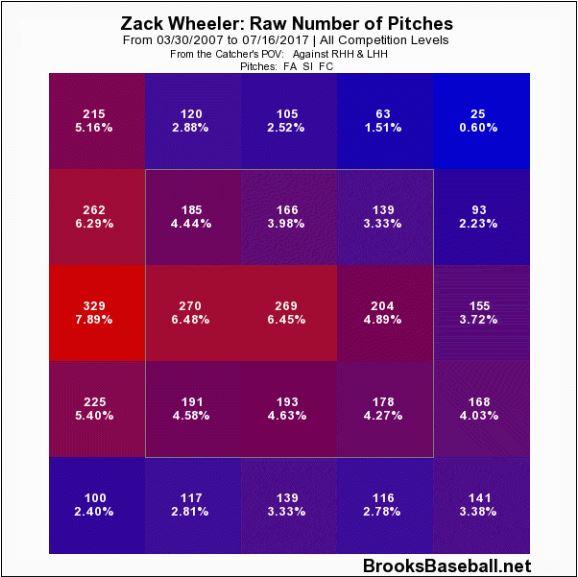

Wheeler is a perfect example of the difference between just being able to throw the ball over the strike zone and having precise command of where the pitch is going. He can throw for strikes, particularly with his fastball:

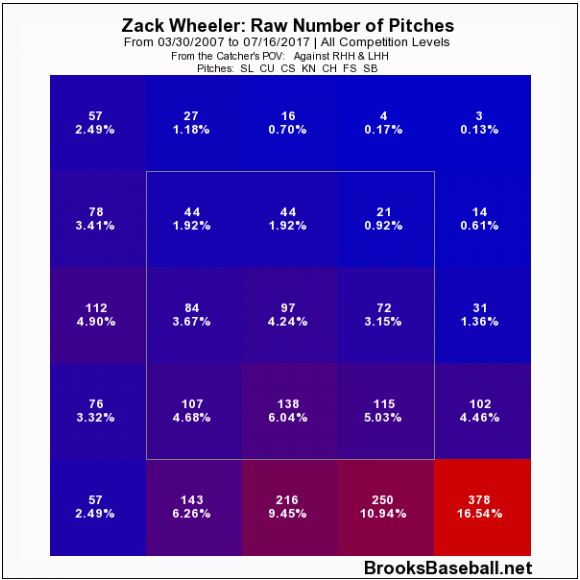

When you throw a 95+ mph fastball in the strike zone, you’re going to get some outs. Of course, major league hitters are good enough to catch up to 95 mile per hour heat unless a pitcher can mix in some breaking balls. This is where Wheeler breaks down. Like Collins said, Wheeler needs to be able to throw his breaking ball for strikes more often:

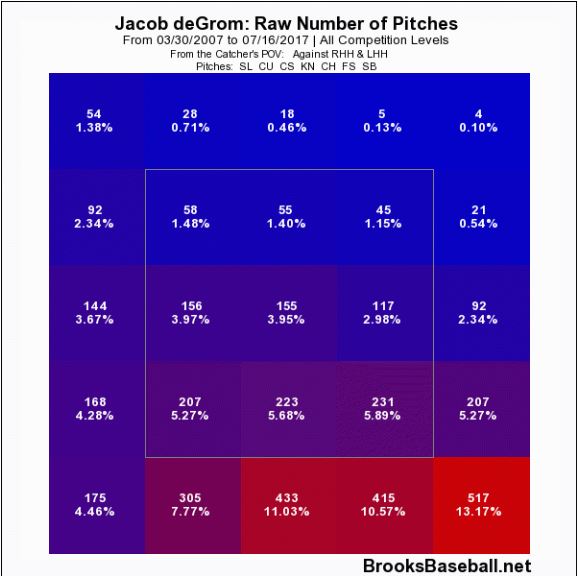

Notice how brightly that lower-right corner stands out on the heat map? For comparison, here is deGrom’s heat map for offspeed pitches:

The actual numbers aren’t that different: deGrom throws a few more offspeed and breaking pitches in the bottom of the zone. The biggest difference is that deGrom uses the area below the strike zone more without having to go low and away. Wheeler’s breaking balls seem much more predictable. It’s easier to put together a scouting report on Wheeler that says “LAY OFF THE BREAKING BALL. IT’S RARELY A STRIKE!” Wheeler’s breaking balls are very predictable for right-handed hitters: he always tries to go down and away.

Breaking balls are effective because they bait the hitter into swinging at a pitch that isn’t moving straight and may not be in the strike zone. When Wheeler throws out of the strike zone, he’s not fooling anybody. Opposing batters only swung at 26.2 percent of Wheeler pitches that PITCHf/x located out of the strike zone. That’s the third worst of any qualified starter. (The other pitch tracker has Wheeler as the second worst starter – he’s extreme enough for both measures to agree.) Some of this may be a smallish sample size, but 76 innings is enough to be certain that Wheeler has problems here.

Wheeler has shown a tendency to get ahead, then throw a curveball way out of the zone trying to get the opposing batter to chase. It’s hard to tell how much Wheeler is struggling to command his curveball and how much he is following a bad game plan. Inexperienced pitchers with high velocity and big breaking balls may be used to overpowering pitchers at lower levels, and Wheeler hasn’t actually spent much time in the big leagues considering all of the rehab time. He had just as much trouble getting hitters to chase after his 2013 call-up and didn’t improve that much in 2014. Wheeler has thrown more sliders this year than he did before the surgery, particularly against right-handers but, again, it’s hard to know whether this is a response to his long recovery or his pre-injury command issues.

The slider was definitely a bright spot in Wheeler’s last start. By the bottom of the fourth inning, the Cardinals were sitting on his fastball and ignoring the curveball. Wheeler turned to his slider against the right-hand heavy lineup and, instead of throwing it low and far away, he was able to locate the slider just off the plate away. He suddenly threw breaking balls that looked like strikes, and he got batters to swing at pitches out of the strike zone. Once he threw credible breaking balls, it was harder for hitters to react to the high fastball.

Wheeler’s next start is later today and he’s facing the Cardinals’ right-hand dominant lineup once again. This may be the perfect chance to see whether he’s taken Collins’ advice and made some bona fide changes to his approach. Can he throw his breaking balls – particularly his slider – close enough to the plate that hitters think it is a strike? Wheeler isn’t just a pitcher coming off Tommy John surgery; he’s a young pitcher who didn’t have as much time to work on the craft of fooling major league hitters because of the injury and lengthy rehab. A more deceptive game plan could help Wheeler get more strikes and go deeper in games, even if his command can only improve a little bit in 2017.

Photo credit: Jeff Curry – USA Today Sports

Great analysis of Wheeler’s weakness. I think (hope) that you accurately identify that he’s inexperienced due to his injuries. Your sentence “Inexperienced pitchers with high velocity and big breaking balls may be used to overpowering pitchers at lower levels, and Wheeler hasn’t actually spent much time in the big leagues considering all of the rehab time.” perfectly expresses my thoughts on Wheeler. Nice article, I really enjoyed reading it.