Erubiel Durazo, 1999: .407/.470/.720 in 134 PA for AAA Tucson

“There is no longer any reason to Free Erubiel Durazo!” — Nate Silver, 2007

Michael Conforto, 2016: .422/.483/.727 in 144 PA for AAA Las Vegas

**

The vanguard generation of internet sabermetricians were outsiders. That’s easy to forget now, in light of the world’s greatest leader’s devastating victory in the Great Analytics War.

Twenty years ago, when online sabermetrics crawled forth from primordial Usenet groups and onto proper websites, few if any teams employed dedicated number-crunchers. Nor did the mainstream media. Former Bill James research assistant Rob Neyer was hired by ESPNet.SportsZone.com in 1996. Baseball Prospectus dot com debuted in 1997. The world was six years away from the publication of Moneyball, which famously portrayed profane shouting matches between an arithmetically enlightened front office and its troglodyte scouting department. To the progressive BP founders, every trade felt like the Diamondbacks dealing for Shelby Miller and every free agent signing felt like the Rockies giving Ian Desmond $70 million to play first base. It’s no wonder early stathead content featured no-holes-barred takedowns of teams’ statistically indefensible roster moves.

Late-’90s MLB teams, as Joe Sheehan wrote recently, seemed incapable of “translating performance based on competition and run environment.” Stated differently, as Sheehan wrote in 2001, “Teams [were] deathly afraid of the unknown, and would rather cast their lot with established mediocrity than with a young player with upside but little in the way of service time.” Sabermetricians were frustrated because they considered minor leaguers’ expected performance to be less an “unknown” than it seemed teams did. Clay Davenport, one of Sheehan’s BP co-founders, coded a system that projected major-league stats from minor-league performances. The Davenport Translations understood that few High-A Lancaster hitters or Low-A Savannah pitchers were destined for greatness. Yet it was clear to statheads that front offices routinely failed to give deserving prospects a shot at real playing time. Back then, nobody online cited the old scouting adage about “not scouting the stat line.”

The zenith of stathead indignation over inexplicable MLB decision-making culminated in the campaign to “Free Erubiel Durazo!” Durazo’s backstory is impressive, but for our purposes it’s enough to say he was signed out of Mexico at age 24 after hitting .350 with 19 home runs in 119 games. The Diamondbacks purchased his Mexican League contract and assigned him to Double-A El Paso for the start of the 1999 season. Durazo proceeded to hit .403/.498/.695 in 65 games. Promoted to Triple-A, he continued his Barry Bonds impersonation with a .407/.470/.720 performance.

With only translated minor-league stats at their disposal — Kevin Goldstein and his direct line to MLB scouts didn’t arrive at BP until 2006 — analysts believed Durazo was the “real deal” who’d earned a place in Arizona’s starting lineup. Durazo debuted in the big leagues on July 26, 1999 and did not stop hitting: .329/.422/.594 over 185 plate appearances. The following year, Durazo was penciled in as the starting first baseman and did not disappoint. He hit .295/.413/.477 in 43 games through May 28. Then he tore cartilage in his wrist. Durazo returned too quickly from the injury and never got back on track. Playing through a wrist injury that required three DL stints (and which, in 2017, might have ended his first season in May), Durazo still managed a hearty .265/.373/.444 line for the year.

During the ensuing winter, Arizona signed 37-year-old Mark Grace to a two-year contract. Grace had performed as well as Durazo in 2000, hitting .280/.394/.429. To the online stats community, the multi-million-dollar signing blocked an inexpensive player in the prime of his career who had done nothing but hit when healthy. Cue the outrage: “If you’re at a D’backs game, start chanting, ‘Free Erubiel Durazo!’ Tear up a pillowcase and put the war cry on it in bold red letters. Call your local sports-talk station on the premise of discussing the NBA playoffs or how many letters Eric Lindros has in his alphabet, then shout the mantra to the world. E-mail sportswriters, both in Phoenix and around the country, with just three little words that will take baseball by storm.” If hashtags existed at the turn of the century, #FreeErubielDurazo would have been Baseball Twitter’s first meme, This Is Fine Dog smiling on a burning Arizona bench.

Relegated to spot starts and pinch-hitting appearances, Durazo still hit .269/.372/.537 over 207 PAs. Of course, Arizona won the 2001 World Series with Grace at first base. In retrospect, it’s hard to argue with a 95-win team giving 553 PAs to a three-time All-Star who hit .298/.386/.466 for the year.

By 2002, the 38-year-old Grace had lost his battle with Father Time. Durazo had 230 points of OPS on Grace at the end of July. From August 1 on, mostly in a starting role, Durazo hit .258/.400/.525. Erubiel Durazo had been freed, wrote Christina Kahrl, “not because someone opened the cage door, but because he beat it open with some Philly-smacking Samson-swinging jawbone action that made it plain that his day has not merely arrived, it was always here. And if it just so happens to reduce Mark Grace to Lead Chain Smoker on the Varsity Pep Squad, well, that’s overdue, too.” In 2003, Durazo signed a three-year contract to play for Moneyball‘s own Oakland Athletics. In his age-29 and -30 seasons, Durazo played every day and hit .289/.384/.475 — a 125 OPS+.

The Free Erubiel Durazo! campaign proved to be the zenith of virulent stathead indignation. In the 2003 denouement, BP published Dayn Perry’s famous “beer and tacos” call for synergy between stats and scouts. Model organizations like the Red Sox under Theo Epstein were succeeding by combining the information gleaned from analytics and old-school baseball men. By 2007, Nate Silver was confident that MLB had become more efficient at awarding plate appearances to the best available players, whether Erubiel Durazo, Kevin Youkilis, or Chad Bradford. Silver attributed this resolution of “asymmetries in the talent distribution process” in part to the rise of sabermetrics. Long gone, we’re told, are the days when an obviously superior player will languish because a team fails to understand his value.

**

In 2015, a rookie named Michael Conforto, the 10th-overall draft pick the year prior, produced a 130 OPS+ by hitting .270/.335/.506 over 194 MLB PAs in his age-22 season. In 2016, the Mets bounced him between the starting lineup, the bench, and Triple-A Las Vegas, where he hit an Erubielian .422/.483/.727 over 144 plate appearances. Sure, those numbers were the product of a superior player slumming in a hitter’s paradise. But forward-thinking front offices had supposedly reached the point of understanding that offensive production which happens in Vegas doesn’t necessarily stay in Vegas ($1, @sethburn).

If what Nate Silver wrote 10 years ago holds true today — “There is no longer any reason to Free Erubiel Durazo!” — minor-leaguers who produce like 1999 Durazo and 2016 Conforto should not only earn big-league promotions the season they plow through the farm, but their parent clubs should provide them with everyday jobs the following year. With young, cost-controlled superstars like Mookie Betts, Francisco Lindor, Corey Seager, and Kris Bryant competing for (and winning) MVP awards, with baseball being dominated by young talent more than in decades, it should behoove general managers to get their productive prospects to the big leagues pronto.

We’ve had minor-league play-by-play data since 2005, so I looked, with Rob McQuown’s generous database wizardry, at minor-league hitters since 2005 who, in at least 60 plate appearances, produced a True Average within 20 percent of the .381 TAv Conforto produced in Triple-A last season. (For reference, 1999 Durazo mashed for a .377 TAv in Triple-A.) This produced a list of 127 players that included 2014 Travis d’Arnaud (.436/.475/.909 at Las Vegas) and 2011 Lucas Duda (.302/.414/.597 at Buffalo).

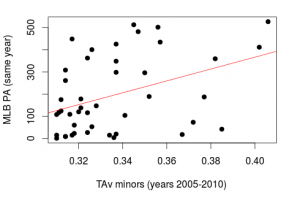

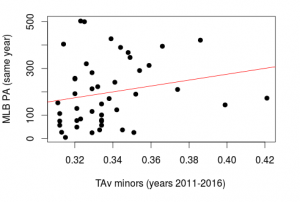

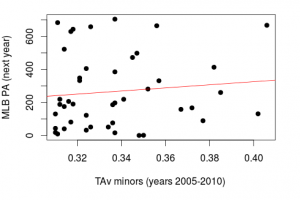

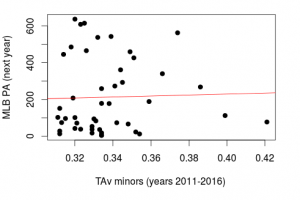

Then I split the 12 years into two samples, one from 2005 to 2010, and the other from 2011 to 2016, and asked two questions: First, are hitting prospects who destroy the minors in Year X promoted to the big leagues in Year X more often now than they used to be? And second, are the guys who mastered the minors in Year X given more MLB plate appearances in Year X+1 than before?

These charts show that hitters who prove they can hit in the minor leagues routinely get promoted to the big leagues, even if only for a cup of coffee. However, the flattening slope of the more recent graph shows the relationship between players’ TAv on the farm and the number of plate appearances they get with the parent club in the same season has actually deteriorated over the last six years.

What’s worse, the moderately positive relationship between mashing in the minors and receiving MLB playing time the following season from 2005 to 2010 has become nearly meaningless since 2011. In other words, a minor league hitter who produced a .311 TAv last year is just as likely to accumulate 200 PAs this year as another hitter who produced a .411 TAv.

The recent data are somewhat skewed by a couple of replacement-level big-leaguers who put up an insanely good month in the PCL. The right-most outlier, with a .421 TAv that’s best in the entire sample, is 2013 Tim Federowicz. That year, when he wasn’t backing up no-hit, great-guy A.J. Ellis with a 231/.265/.356 line for the Dodgers, he was annihilating Albuquerque to the tune of .418/.500/.848. The other extreme TAv belonged to 2013 Met Jordany Valdespin, a Biogenesis suspendee who, like Federowicz, didn’t hit in the big leagues (.188/.250/.316) but put up video game numbers in Las Vegas (.466/.537/.759, a .399 TAv).

That said, the charts seem to show teams from 2005-2010 were more inclined to promote hitters who excelled in the minors than teams are now. In fairness to parent clubs, perhaps we’ve just lived through an especially disappointing 2011-2016 prospect-bust era: Carlos Peguero, Dustin Ackley, Grant Green, Jesus Montero, Mike Olt, Aaron Hicks, Mike Zunino — goodness, I’m sorry, Mariners fans — all appear on this list and were considered some level of can’t-miss by minor-league analysts. On any list of minor-league studs, some will turn out to be Ryan Howard (.337 TAv in 2005), and some will turn out to be Matt LaPorta (.337 TAv in 2010). Some are Matt Joyce (.314 TAv in 2010) and some are Kila Ka’aihue (.316 TAv in 2009, and the beneficiary of his own “Free Player X” campaign). There really is such thing as a quad-A player, and it’s not always possible to identify them before they fail in the majors.

In any event, there is not strong evidence that over the last six years, MLB teams are giving their promising youngsters more playing time than they used to.

**

For 2017, in a transaction reminiscent of the 2001 D’backs signing Mark Grace, the Mets picked up the $13 million club option on 30-year-old outfielder Jay Bruce, like Conforto a lefty-swinging slugger, but whose career OBP is 17 points lower than Conforto’s rookie mark. Between Bruce, the $15 million Curtis Granderson, and the $22.5 million Yoenis Cespedes, there have been few regular at-bats for the minimum-salaried Conforto. There was a pervasive feeling around the Mets that if Juan Lagares and Brandon Nimmo had been healthy to start the season, Conforto wouldn’t have even made the team. To wit, public-address announcer Howie Rose symbolically (if inadvertently) skipped over Conforto during player introductions on Opening Day. Weeks ago, the call to #FreeMichaelConforto were heard throughout the land.

Yet Bruce has done his best to elicit apologies from those (from everybody) who hated the Mets’ decision to pay him and play him over a rising star. Also reminiscent of the D’backs’ Grace signing, Bruce is earning his contract and then some. Through April 22, he was tied for third in MLB with six home runs. His .360 OBP and .576 SLG were both career-high marks. Even if Bruce’s performance may be unsustainable, it’s not illusory: He’s already produced 0.7 WARP in the 2017 season’s first 18 games. Of course, Michael Conforto has hit .312/.400/.625 and produced 1.1 WARP over the same timeframe.

Sometimes, playing-time crunches work themselves out. Starting center fielder Curtis Granderson is stumbling his way into retirement with a .159/.217/.270 triple-slash. Jose Reyes was talked about as a part-time outfielder this spring; he’s off to an even worse .095/.186/.127 start. Meanwhile, Yoenis Cespedes is suffering from a hamstring injury. Lucas Duda and Wilmer Flores, the two Mets with the most experience at first base, are both on the disabled list, forcing Bruce to the cold corner. Conforto’s started each of the last five games. Hitting .368/.455/.684 in those starts is a great sign. Some believe his leadoff home run and 3-for-4 performance against Max Scherzer in this past Sunday night’s nationally televised ESPN game should be the last time his status as an everyday player is ever questioned.

“Should” is the operative term. If, after this early-season success, Cespedes and Duda’s eventual returns push Conforto back to the bench — or, incredibly, Las Vegas — the decision wouldn’t be out of line with recent MLB trends. But it would spur the calls to #FreeMichaelConforto, louder than ever.

Thanks to Rob McQuown for research assistance

Photo credit: Bill Streicher – USA Today Sports

2 comments on “Free Michael Conforto(?)”

Comments are closed.